Inquiring minds want to know – how does banding a seabird impact their conservation? The research team on Pond Island NWR took some time to break down the process and explain the importance of this vital conservation tool.

Banding (or ringing, as they call it in Europe) is a vital part of any bird research. It helps us keep track of individual birds of all species across countless studies around the world.

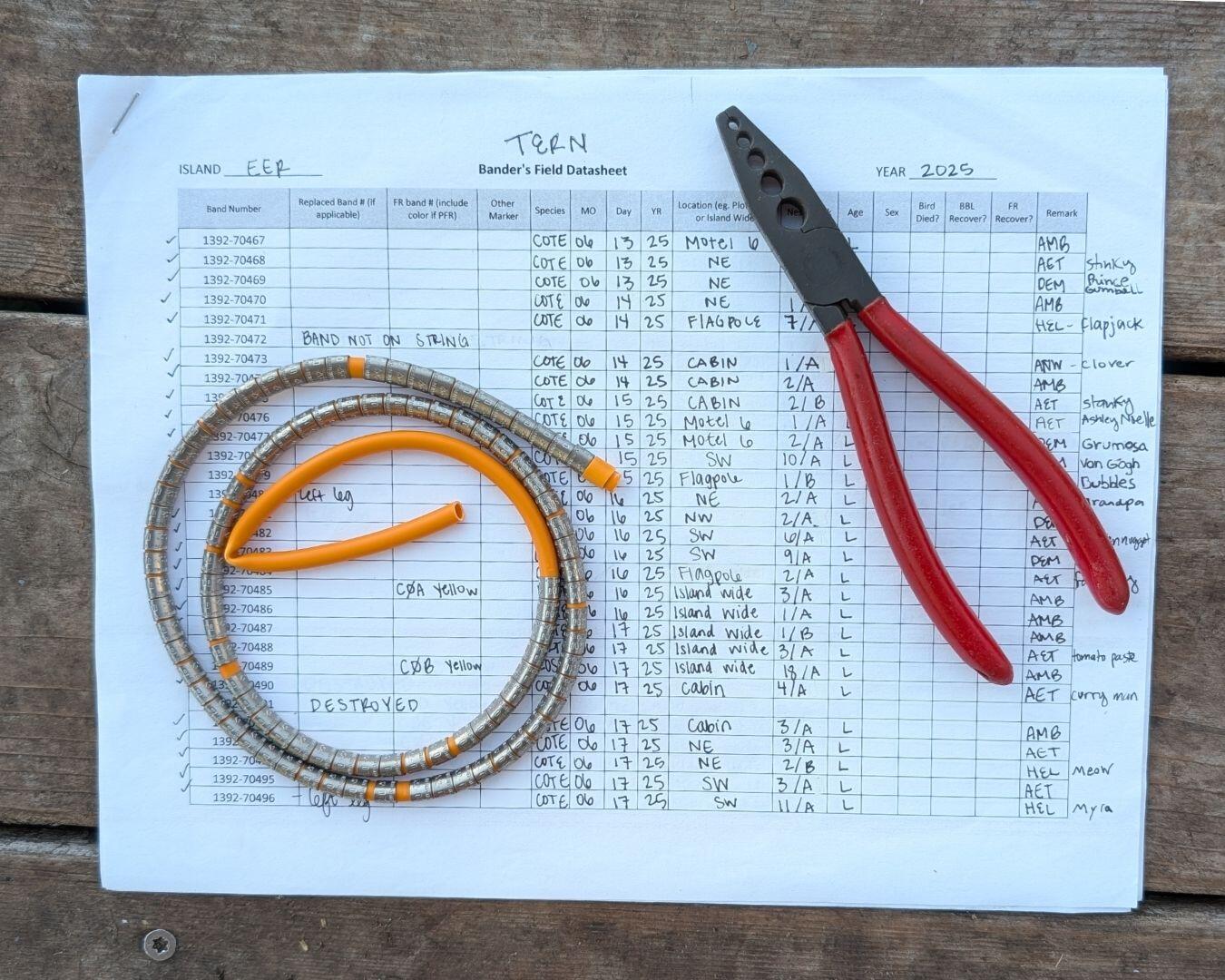

Different types of bands exist, including Plastic Field Readable (PFRs), Metal Field Readable (MFRs), and plastic color bands or flags. Field-Readable bands are typically a combination of 3-4 letters or numbers and placed on more heavily monitored species like Roseate Terns, Arctic Terns, and puffins. Seeing colored flags on birds can be especially exciting, as they are color-coded by country. Green flags signify a bird that was banded in the United States. When we see an orange flag, we know that bird was banded in Argentina. The birds we observe in our study plots here on Pond Island are all banded with a “BBL” metal band. This a serialized, unique band from the Bird Banding Lab (BBL). The number on each band acts similarly to a social security number. It’s usually a 4-number prefix followed by a 5-number suffix.

Pond Island is home to a colony of terns, and their legs stay about the same size throughout their life. This means, in most cases, a chick can be banded the day they hatch – though we wait until they are dry and downy before handling. A band is removed from a "string" of bands before using banding pliers to attach it to the bird’s right leg. Birds can be banded on their upper right, upper left, lower right, or lower left leg. We opt for the lower leg, as it is easier to see. Seabird Institute researchers have the custom of giving the bird a name when the band is applied, though the number on the band is the formal method of identification. After the bird is banded, all data collected from that bird is archived with the Bird Banding Lab and our own seabird database.

Island Introductions

Conserving seabirds along coastal Maine is the ultimate summer adventure for avian enthusiasts and birdy biologists. Follow along as we get to know the research teams safeguarding seabirds along Maine’s coast.

Stratton Island is a 24-acre island just a few miles off the coast of Prout’s Neck in Scarborough, Maine. It is the southernmost and westernmost field station established by the Seabird Institute, operating with key support from the Prout’s Neck Audubon Society. Tern restoration began on the island in 1986, and today the island is home to Maine’s largest Roseate Tern colony. This year’s research team has enjoyed banding birds by day and exploring tidepools by night. Research Assistant, Joe Sweeney, said he’s discovered how interesting working with seabirds can be and excited to stay connected to wildlife far beyond the end of the field season in Maine.

Outer Green Island is a small island located five miles east of Portland, Maine. Restoration began on the island in 2002. The use of decoys paired with human deterrence against gulls has helped restore over 1,000 pairs of nesting terns as well as guillemots and eiders to the island. These birds have been surprising the research team all season. Research Assistant, Emerald Lin, has enjoyed the feistiness that Black Guillemot chicks bring to the island. Curtis Mahon, Island Supervisor, has been amazed discovering where these species nests. Guillemots, for example, have been found in the “tiniest little holes in the rocks or a skinny ledge.”

Engagement that Inspires

The Seabird Institute’s Adopt-a-Puffin Program has brought the story of Eastern Egg Rock puffins to thousands of adopters for more than two decades. Long-term adopters have followed their puffins for many years and are always anxious to read their puffin's annual update upon renewal. This year, a long-term adopter planned a trip with her family to visit Maine and, maybe more importantly, her adopted puffin on Eastern Egg Rock. After a very puffin-y puffin cruise with our partners on the Hardy Boat, the family stopped by the Todd Wildlife Sanctuary and Project Puffin Visitor Center. What began as a single puffin adoption has grown to engage and inspire three generations of her family!

Interested in learning the story of a real Eastern Egg Rock puffin? Now is the perfect time to enroll in the Adopt a Puffin program with a $100 gift. Once enrolled, you’ll get to know a real puffin that lives on Eastern Egg Rock. You will receive a biography of a puffin, including its most recent activities, and a colorful certificate of adoption displaying your name or the name of its recipient. Adopt Now!